Zakir Husain (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

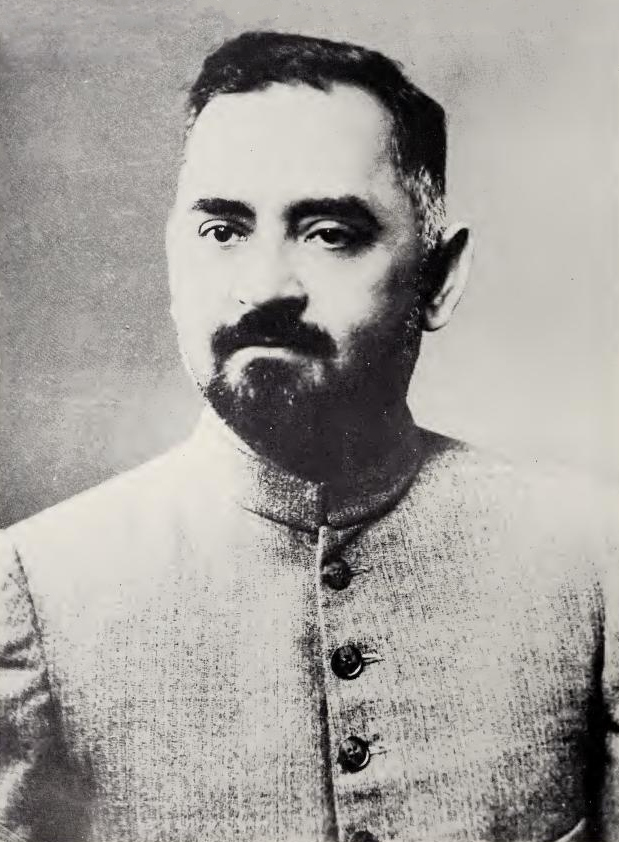

Zakir Husain Khan (8 February 1897 – 3 May 1969) known as Dr. Zakir Husain, was an Indian

education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

ist and politician who served as President of India

The president of India ( IAST: ) is the head of state of the Republic of India. The president is the nominal head of the executive, the first citizen of the country, as well as the commander-in-chief of the Indian Armed Forces. Droupadi Mur ...

from 13 May 1967 until his death on 3 May 1969.

Born into an Afridi Pashtun

The Afrīdī ( ps, اپريدی ''Aprīdai'', plur. ''Aprīdī''; ur, آفریدی) are a Pashtun tribe present in Pakistan, with substantial numbers in Afghanistan. The Afridis are most dominant in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal ...

family in Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India ...

, Husain studied in Etawah

Etawah also known as Ishtikapuri is a city on the banks of Yamuna River in the state of Western Uttar Pradesh in India. It is the administrative headquarters of Etawah District. Etawah's population of 256,838 (as per 2011 population census) m ...

, the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College

Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College ( ur, Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan-e-Hind, italics=yes) was founded in 1875 by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, initially as a primary school, with the intention of taking it to a college level institution, known as Muhammed ...

, Aligarh

Aligarh (; formerly known as Allygarh, and Kol) is a city in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. It is the administrative headquarters of Aligarh district, and lies northwest of state capital Lucknow and approximately southeast of the cap ...

and the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

from where he obtained a doctoral degree

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

in economics. He was a founding member of the Jamia Milia Islamia

Jamia Millia Islamia () is a central university located in New Delhi, India. Originally established at Aligarh, United Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh, India) during the British Raj in 1920, it moved to its current location in Okhla in ...

of which he served as Vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

during 1926 to 1948. He was closely associated with Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

and was chairman of the Basic National Education Committee which framed a new educational policy known as Nai Talim

Nai Talim, or Basic Education, is a principle which states that knowledge and work are not separate. Mahatma Gandhi promoted an educational curriculum with the same name based on this pedagogical principle.

It can be translated with the phrase ...

with its emphasis on free and compulsory education in the first language

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tongu ...

. Appointed Vice Chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University in 1948, he helped retain it as a national institution of higher learning. For his services to education, he was awarded the Padma Vibhushan

The Padma Vibhushan ("Lotus Decoration") is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India, after the Bharat Ratna. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service". All persons without ...

in 1954 and was a nominated member of the Indian Parliament

The Parliament of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of the ...

during 1952 to 1957.

Husain served as Governor of Bihar

The governor of Bihar is a nominal head and representative of the President of India in the state of Bihar. The Governor is appointed by the President for a term of 5 years. Phagu Chauhan is the current governor of Bihar. Former President Zaki ...

from 1957 to 1962 and was elected the Vice President of India

The vice president of India (IAST: ) is the deputy to the head of state of the Republic of India, i.e. the president of India. The office of vice president is the second-highest constitutional office after the president and ranks second in the ...

in 1962. The following year, he was conferred the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distinctio ...

. He was elected president in 1967, succeeding Dr. S. Radhakrishnan

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (; 5 September 1888 – 17 April 1975), natively Radhakrishnayya, was an Indian philosopher and statesman. He served as the 2nd President of India from 1962 to 1967. He also 1st Vice President of India from 1952 ...

, and became the first Muslim to hold the highest constitutional office in India. He was also the first incumbent to die in office in 1969 and has had the shortest tenure of any President. His mazar Mazar of Al-Mazar may refer to:

*Mazar (mausoleum); often but not always Muslim mausoleum or shrine.

Places

*Mazar (toponymy), a component of Arabic toponyms literally meaning shrine, grave, tomb, etc.

*Mazar, Afghanistan, a village in Balkh Pro ...

lies in the campus of the Jamia Milia Islamia in Delhi.

An author and translator of several books into Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

''

children's books

A child ( : children) is a human being between the stages of birth and puberty, or between the developmental period of infancy and puberty. The legal definition of ''child'' generally refers to a minor, otherwise known as a person younge ...

, Husain has been commemorated in India through postage stamps and several educational institutions, libraries, roads and Asia's largest rose garden that have been named after him.

Early life and education

Husain was born inHyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India ...

in 1897 and is of Afridi Pashtun

The Afrīdī ( ps, اپريدی ''Aprīdai'', plur. ''Aprīdī''; ur, آفریدی) are a Pashtun tribe present in Pakistan, with substantial numbers in Afghanistan. The Afridis are most dominant in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal ...

descent, his forefathers having settled in the town of Qaimganj

Kaimganj is a town in Farrukhabad district in the Indian State of Uttar Pradesh. Kaimganj Railway Station is a major station between Farrukhabad and Kasganj on Rajputana railway link of North Eastern Railway.

Description

Kaimganj is just 10&n ...

in the Farrukhabad district

Farrukhabad district is a district of Uttar Pradesh state in Northern India. The town of Fatehgarh is the district headquarters. The district is part of Kanpur Division.

Farrukhabad is situated between Lat. 26° 46' N & 27° 43' N and Lo ...

of modern Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh (; , 'Northern Province') is a state in northern India. With over 200 million inhabitants, it is the most populated state in India as well as the most populous country subdivision in the world. It was established in 1950 ...

. His father, Fida Husain Khan, moved to the Deccan and established a successful legal career in Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India ...

where he settled in 1892. Husain was the third of seven sons of Fida Khan and Naznin Begum. He was homeschooled

Homeschooling or home schooling, also known as home education or elective home education (EHE), is the education of school-aged children at home or a variety of places other than a school. Usually conducted by a parent, tutor, or an onlin ...

in the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

, Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

''

primary school education at the Sultan Bazaar school in Hyderabad. Following his father's death in 1907 Husain's family shifted back to Qaimganj and he was enrolled at the Islamia High School in

In 1920,

In 1920,

Etawah

Etawah also known as Ishtikapuri is a city on the banks of Yamuna River in the state of Western Uttar Pradesh in India. It is the administrative headquarters of Etawah District. Etawah's population of 256,838 (as per 2011 population census) m ...

. Husain's mother and several members of his extended family died in a plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

epidemic in 1911. Having matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

in 1913, he joined the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College

Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College ( ur, Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan-e-Hind, italics=yes) was founded in 1875 by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, initially as a primary school, with the intention of taking it to a college level institution, known as Muhammed ...

at Aligarh

Aligarh (; formerly known as Allygarh, and Kol) is a city in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. It is the administrative headquarters of Aligarh district, and lies northwest of state capital Lucknow and approximately southeast of the cap ...

and later, in preparation for a medical degree, at the Lucknow Christian College

Lucknow Christian College is a graduate and post-graduate college located in Golaganj, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. It is affiliated with the University of Lucknow.

Overview

Lucknow Christian College was established in 1862. It is an Inst ...

enrolling for a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

degree. A bout of illness led to him having to discontinue his studies and a year later he rejoined the college at Aligarh. Husain graduated in 1918 with philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

, English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

and economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes ...

. He was elected vice president of the college's students' union and won prizes for his debating skills. Husain pursued the disciplines of law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

and economics for his post-graduate studies. Having obtained his master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

in 1920, he was appointed as a lecturer at the college.

Family

Of Husain's six brothers,Yusuf Husain

Yusuf Husain Khan (1902–1979), born in Hyderabad, Hyderabad State, British India, was a historian, scholar, educationist, critic and author. He mastered the languages of Arabic, English, French, Urdu, Hindi and Persian.

Early life and educa ...

became a historian and a winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award

The Sahitya Akademi Award is a literary honour in India, which the Sahitya Akademi, India's National Academy of Letters, annually confers on writers of the most outstanding books of literary merit published in any of the 22 languages of the ...

who served as Pro Vice-Chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University. Mahmud Husain was closely associated with the Pakistan Movement, becoming Minister of Education in the Government of Pakistan

The Government of Pakistan ( ur, , translit=hakúmat-e pákistán) abbreviated as GoP, is a federal government established by the Constitution of Pakistan as a constituted governing authority of the four provinces, two autonomous territorie ...

and Vice-Chancellor at Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; bn, ঢাকা, Ḍhākā, ), formerly known as Dacca, is the capital and largest city of Bangladesh, as well as the world's largest Bengali-speaking city. It is the eighth largest and sixth most densely populated city i ...

and Karachi Universities. His son, General Rahimuddin Khan

Rahimuddin Khan (21 July 1926 – 22 August 2022) was a general of the Pakistan Army who served as the 4th Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee from 1984 to 1987, after serving as the 7th governor of Balochistan from 1978 to 1984. He also ...

went on to become Pakistan's Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC) ( ur, ) is, in principle, the highest-ranking and senior most uniformed military officer, typically at four-star rank, in the Pakistan Armed Forces who serves as a Principal Staff Officer and ...

and later Governor of Balochistan

The Governor of Balochistan is the head of the province of Balochistan, Pakistan. The post was established on 1 July 1970, after the dissolution of West Pakistan province and the end of One Unit. Under Pakistan's current parliamentary system, the ...

. Masud Husain, the nephew from his eldest brother, became Professor Emeritus in Social Sciences at the Aligarh Muslim University and later Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia. In 1915, while still pursuing his graduation, Husain married Shahjahan Begum with whom he had two daughters, Sayeeda Khan and Safia Rahman.

Safia married Dr. Zil-ur-Rahman, a professor of physics at the Aligarh Muslim University while Sayeeda married Khurshed Alam Khan

Khurshed Alam Khan (5 February 1919 – 20 July 2013) was an Indian politician and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress political party.Salman Khurshid

Salman Khurshid Alam Khan (born 1 January 1953) is an Indian politician, designated senior advocate, eminent author and a law teacher. He was the Cabinet Minister of the Ministry of External Affairs. He belongs to the Indian National Congress. ...

became India's External Affairs Minister in 2012.

Career

Sheikh-ul-Jamia, Jamia Milia Islamia (1926-1948)

In 1920,

In 1920, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

visited the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College

Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College ( ur, Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan-e-Hind, italics=yes) was founded in 1875 by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, initially as a primary school, with the intention of taking it to a college level institution, known as Muhammed ...

in Aligarh

Aligarh (; formerly known as Allygarh, and Kol) is a city in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. It is the administrative headquarters of Aligarh district, and lies northwest of state capital Lucknow and approximately southeast of the cap ...

where he urged non-cooperation with the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

. In response to Gandhi's appeal, a group of students and faculty joined the Non-Cooperation Movement

The Non-cooperation movement was a political campaign launched on 4 September 1920, by Mahatma Gandhi to have Indians revoke their cooperation from the British government, with the aim of persuading them to grant self-governance.

. In October 1920 they established the Independent National University aimed at imparting education free from colonial influence. Later renamed the Jamia Millia Islamia, it shifted in 1925 from Aligarh to Delhi. Husain was one of the founders of this private university which had Maulana Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; ar, محمد علي; 1874 – 13 October 1951) was an Indian writer, scholar, and leading figure of the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement.

Biography

Ali was born in Murar, Kapurthala State (now in Ludhiana district, Punja ...

as its first “Sheikh-ul-Jamia” (vice-chancellor) and Hakim Ajmal Khan

Mohammad Ajmal Khan (11 February 1868 – 29 December 1927), better known as Hakim Ajmal Khan, was a physician in Delhi, India, and one of the founders of the Jamia Millia Islamia University. He also founded another institution, Ayurved ...

as the first "Amir-i-Jamia” (chancellor). Jamia, as the Turkish educationist Halide Edib

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a f ...

noted, had two purposes: “First, to train the Muslim youth with definite ideas of their rights and duties as Indian citizens. Second, to coordinate Islamic thought and behaviour with Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

. The general aim is to create a harmonious nationhood without Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

losing their Islamic identity. In its aim, if not always in its procedure, it is nearer to Gandhian Movement than any other Islamic institution I have come across.” In its early years, Jamia faced shortage of funds and its continued existence was uncertain especially after the Non-Cooperation Movement and the Khilafat Committee closed down.

Husain left for Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

in 1922 to do a doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

in economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes ...

from the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

. Supervised by Werner Sombart

Werner Sombart (; ; 19 January 1863 – 18 May 1941) was a German economist and sociologist, the head of the "Youngest Historical School" and one of the leading Continental European social scientists during the first quarter of the 20th century. ...

, his thesis on the agrarian structure in British India was accepted summa cum laude in 1926. During his time in Berlin, Husain collaborated with Alfred Ehrenreich Alfred Ehrenreich (1882–1931) was a Moravian-born American immigrant who developed and advanced the trade of wide scale shark harvesting. He had been fascinated by sharks from an early age. He helped to start a business in America that caught and ...

to translate into German thirty-three of Gandhi's speeches which were published in 1924 as ''Die Botschaft des Mahatma Gandhi''. Husain got published the ''Diwan-e-Ghalib

Diwan-e-Ghalib is a famous poetry book written by the famous Persian and Urdu poet Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib. It is a collection of the ghazals of Ghalib. Though it does not include all of his ghazals as he was too choosy to include them all, ...

'' in 1925 and the ''Diwan-i-Shaida'', a collection of poetry by Hakim Ajmal Khan

Mohammad Ajmal Khan (11 February 1868 – 29 December 1927), better known as Hakim Ajmal Khan, was a physician in Delhi, India, and one of the founders of the Jamia Millia Islamia University. He also founded another institution, Ayurved ...

in 1926. He returned to India in 1926 and succeeded Abdul Majeed Khwaja

Abdul Majeed Khwaja (1885 – 2 December 1962) was an Indian lawyer, educationist, social reformer and freedom fighter from Aligarh. In 1920, he along with others founded Jamia Millia Islamia and later served its vice chancellor and chancell ...

as “Sheikh-ul-Jamia”. He was joined by Mohammad Mujeeb

Mohammad Mujeeb (1902-1985) was an Indian writer of English and Urdu literature, educationist, scholar and the vice chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi.

Early life and education

Mujeeb was born in 1902 to Mohammad Naseem, a wealthy barris ...

and Abid Husain – the latter becoming the university registrar

A registrar is an official keeper of records made in a register. The term may refer to:

Education

* Registrar (education), an official in an academic institution who handles student records

* Registrar of the University of Oxford, one of the se ...

. Husain travelled across India soliciting funds for the Jamia and got financial support from Mahatma Gandhi, the Bombay philanthropist Seth Jamal Mohammed, Khwaja Abdul Hamied

Khwaja Abdul Hamied FCS, FRIC (31 October 1898 – 23 June 1972) was an Indian industrial and pharmaceutical chemist who founded Cipla, India's oldest pharmaceutical company in 1935. His son, Yusuf Hamied headed the company after him f ...

the founder of the pharmaceutical firm Cipla

Cipla Limited (stylized as Cipla) is an Indian multinational pharmaceutical company, headquartered in Mumbai. Cipla primarily develops medicines to treat respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, diabetes, depression and many oth ...

and the Nizam of Hyderabad among others.

In 1928, a National Education Society was established to manage the affairs of the Jamia. Zakir Husain became its secretary. To be a life member of the society, members pledged their services to it for 20 years with a salary that could not exceed Rs.150. Husain was one of the 11 initial members who took the pledge. The society adopted a constitution for the university which stipulated that the Jamia would neither seek nor accept any help from the colonial administration, and that it would treat all religions impartially. Husain himself identified the aim of the Jamia as being to “keep alive Islamic culture and education and also help in the realization of the ideal of a common nationhood and the achievement of the freedom of the country �� nd thatthe Jamia’s objectives are Islamic education Islamic education may refer to:

*Islamic studies

Islamic studies refers to the academic study of Islam, and generally to academic multidisciplinary "studies" programs—programs similar to others that focus on the history, texts and theolo ...

, the love of independence and service to Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

''

Gulmohar

''Delonix regia'' is a species of flowering plant in the bean family Fabaceae, subfamily Caesalpinioideae native to Madagascar. It is noted for its fern-like leaves and flamboyant display of orange-red flowers over summer. In many tropical par ...

Avenue in Jamia Nagar. Husain was opposed to the policy of separate electorates for Muslims and was a political opponent of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

, who vetoed the Congress proposal to include Husain as a member of the Interim Government in 1946. Husain however convinced Jinnah to attend the Jamia's silver jubilee celebration on 17 November 1946. At a time of rising animosity between the Congress and the Muslim League and worsening inter-communal relations, the celebration was attended by Jinnah, his sister Fatima and Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan ( ur, ; 1 October 1895 – 16 October 1951), also referred to in Pakistan as ''Quaid-e-Millat'' () or ''Shaheed-e-Millat'' ( ur, lit=Martyr of the Nation, label=none, ), was a Pakistani statesman, lawyer, political theoris ...

from the Muslim League and Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

, Maulana Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following Ind ...

and C. Rajagopalachari

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 – 25 December 1972), popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji (Rajaji'', the Scholar Emeritus''), was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and independence activis ...

of the Congress. In a plea to the assembled leaders, Husain said

“"You, gentlemen, are the stars of the political firmament. You have a secure place in the hearts of millions of people. Taking advantage of your presence here, I wish to submit in great sorrow a few words for your consideration on behalf of the educational workers. The fire of hatred is fast spreading which makes it seem mad to tend to the garden of education. This fire is burning in a noble and humane land. How will the flowers of nobility and sensibility grow in its midst? How will we be able to improve human standards which lie today at a level far lower than that of the beasts? How shall we produce new servants devoted to the cause of education? How can you protect humanity in a world of animals? ... . An Indian poet has remarked that every child who comes to this world brings along the message that God has not yet lost faith in man. But have our countrymen so completely lost faith in themselves that they wish to crush these innocent buds before they blossom? For God's sake sit together and extinguish this fire of hatred. This is not the time to ask who is responsible for it and what is its cause. The fire is raging. Please extinguish it. For God's sake do not allow the very foundations of civilised life in this country to be destroyed."

Basic National Education Committee (1937)

In October 1937, an All-India National Education Conference was held atWardha

Wardha is a city and a municipal council in Wardha district in the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the administrative headquarters of Wardha district. Wardha gets its name from the Wardha River which flows at the north, west and south bounda ...

under Mahatma Gandhi which sought to establish a policy for basic education in India. The conference appointed a Basic National Education chaired by Husain (also known as the Zakir Husain committee) which was tasked with preparing the detailed scheme and syllabus for this policy. The committee submitted its report in December 1937 and formulated the Wardha Scheme of Basic National Education or Nai Talim

Nai Talim, or Basic Education, is a principle which states that knowledge and work are not separate. Mahatma Gandhi promoted an educational curriculum with the same name based on this pedagogical principle.

It can be translated with the phrase ...

.

The policy, inter alia, proposed teaching craft work in schools, instilling ideals of citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

, and its establishment as a self-supporting scheme. It proposed seven years of free and compulsory basic education in the mother tongue, the teaching of crafts, music and drawing and learning the Hindustani language

Hindustani (; Devanagari: ,

*

*

*

* ; Perso-Arabic: , , ) is the '' lingua franca'' of Northern and Central India and Pakistan. Hindustani is a pluricentric language with two standard registers, known as Hindi and Urdu. Thus, the lang ...

. It also proposed a comprehensive plan for the training of teachers and framed its curriculum.

The Congress party in its Haripura

Haripura is a village located near Kadod town in the Surat district of Gujarat, India. It is around 13 kilometres north east of Bardoli. During the Indian independence movement, it was the venue of annual session of the Indian National Congress ...

session of 1938 accepted the scheme and sought to implement it nationwide. An All-India Education Board (the Hindustani Talimi Sangh) was established to implement the scheme under Husain and E.W. Aryanayakam with Gandhi as its overall supervisor. Husain remained the President of the Hindustani Talimi Sangh from 1938 to 1950 when he was succeeded by Kaka Kalelkar

Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar (1 December 1885 – 21 August 1981), popularly known as Kaka Kalelkar, was an Indian independence activist, social reformer, journalist and an eminent follower of the philosophy and methods of Mahatma Gandhi.

B ...

. The scheme was wholly opposed by the Muslim League which saw the scheme as an attempt to gradually destroy Muslim culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predomi ...

in India and the focus on Hindustani language as a ploy to replace Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

''

Sanskritized Hindi. The Congress party's argument that the scheme had been formulated by Husain was rejected by the Muslim League in its

Husain, who had suffered a mild

Husain, who had suffered a mild

Husain's tomb was built in 1971 and was designed by Habib Rahman. Its architecture reflects the influence of Bauhaus aesthetics on traditional Indian styles as seen in its eight curved, reinforced concrete walls topped by rough cut

Husain's tomb was built in 1971 and was designed by Habib Rahman. Its architecture reflects the influence of Bauhaus aesthetics on traditional Indian styles as seen in its eight curved, reinforced concrete walls topped by rough cut

Patna

Patna (

), historically known as Pataliputra, is the capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Patna had a population of 2.35 million, making it the 19th largest city in India. ...

session of 1939 where it declared that “the mere fact that the Principal of Jamia Millia at Delhi has taken a prominent part in the preparation of the scheme does not prove that it is not unsuited to the Muslims”.

India's National Policy on Education

The National Policy on Education (NPE) is a policy formulated by the Government of India to promote and regulate education in India. The policy covers elementary education to higher education in both rural and urban India. The first NPE was prom ...

of 1968, 1988 and 2020 all draw on the ideas contained in the Wardha Scheme of Basic National Education.

Following the Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

, Husain was almost killed in communal violence at the Jalandhar railway station while he was on his way to Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

- an experience he described twelve years later to his friend Abdul Majid Daryabadi

Abdul Majid Daryabadi (16 March 1892 – 6 January 1977) was an Islamic scholar, philosopher, writer, critic, researcher, journalist and exegete of the Quran in Indian subcontinent in 20th century. He was as one of the most influential Indian Mus ...

. On his return to Delhi, Husain worked to help the victims of rioting in Delhi. The Jamia Milia Islamia's buildings at Karol Bagh

Karol Bagh is a neighbourhood in Central District of Delhi, India. It is a mixed residential and commercial neighborhood known for shopping streets such as the Ghaffar Market and Ajmal Khan Road.

It was home to the Karol Bagh Lok Sabha cons ...

were looted and destroyed in the violence in Delhi.

Vice-Chancellor, Aligarh Muslim University (1948-1956)

Husain was appointed Vice Chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University in 1948, succeeding Nawab Ismail Khan. The university had been closely associated with thePakistan Movement

The Pakistan Movement ( ur, , translit=Teḥrīk-e-Pākistān) was a political movement in the first half of the 20th century that aimed for the creation of Pakistan from the Muslim-majority areas of British India. It was connected to the per ...

and had been a stronghold of the Muslin League. It was therefore perceived as a center of pro-Pakistan feeling and a threat to secular India. Maulana Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following Ind ...

, the Union Minister of Education, tasked Husain with leading the university so that it could be retained as a national institution of higher education.

Husain, who had served as a member of the Universities Commission between December 1948 and August 1949 however took regular charge only in early 1950 as he was incapacitated following a heart attack in October 1949. He set to work, attempting to dissociate the university from its past association with the Muslim League and restoring school discipline

School discipline relates to actions taken by teachers or school organizations toward students when their behavior disrupts the ongoing educational activity or breaks a rule created by the school. Discipline can guide the children's behavior or ...

. Students released from prison for involvement in Communist activism were readmitted and socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

and communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

from across North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

took up the vacancies created by the departure of Muslim nationalists for Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. Husain also filled up vacant faculty positions with eminent academicians.

In 1951, Parliament enacted the Aligarh Muslim University (Amendment) Act which converted the university from a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

, aided university to an autonomous institution of the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, ...

, fully maintained by it. This ensured stability in the university's finances while also allowing it autonomy in governance. By the end of his tenure, Husain had turned around the fortunes of the university, helping it overcome the uncertainty it faced in independent India

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

and become a national institution under the patronage of the Government of India.

Husain served as a nominated Member of the Rajya Sabha from 3 April 1952 to 2 April 1956 and was renominated in 1956, serving until his resignation on 6 July 1957 following his appointment as the Governor of Bihar. For his services in the areas of culture and education Husain was conferred the Padma Vibhushan

The Padma Vibhushan ("Lotus Decoration") is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India, after the Bharat Ratna. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service". All persons without ...

in 1954. Throughout the 1950s he was associated with various organizations working in the field of education. He was chairman, India Committee, International Students Service (1955), the World University Service

The World University Service (WUS) is an international organisation founded in 1920 in Vienna as an offshoot of the World Student Christian Federation to meet the needs of students and academics in the aftermath of World War I. After World War II, ...

, Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

during 1955-57 and was a member of the Central Board of Secondary Education

The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) is a national level board of education in India for public and private schools, controlled and managed by the Government of India. Established in 1929 by a resolution of the government, the Board ...

(1957). He served on the executive board of the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

during 1957–58.

Governor of Bihar (1957-1962)

Husain was theGovernor of Bihar

The governor of Bihar is a nominal head and representative of the President of India in the state of Bihar. The Governor is appointed by the President for a term of 5 years. Phagu Chauhan is the current governor of Bihar. Former President Zaki ...

from 6 July 1957 to 11 May 1962. Contrary to the advice of the then Chief Minister of Bihar, Shri Krishna Sinha

Shri Krishna Sinha (21 October 1887 – 31 January 1961), also known as Shri Babu, was the first chief minister of the Indian state of Bihar (1946–61). Except for the period of World War II, Sinha was the chief minister of Bihar from the time ...

, Governor Husain, who was also Chancellor of Patna University

Patna University is a public state university in Patna, Bihar, India. It was established on 1 October 1917 during the British Raj. It is the first university in Bihar and the seventh oldest university in the Indian subcontinent in the modern e ...

reappointed for a second term its serving Vice-Chancellor. In response, the state government considered amending the law to require the governor to appoint a vice-chancellor as advised by the chief minister

A chief minister is an elected or appointed head of government of – in most instances – a sub-national entity, for instance an administrative subdivision or federal constituent entity. Examples include a state (and sometimes a union terri ...

. Husain however threatened to resign rather than assent to such an amendment forcing the government to drop its plans. In later appointments made as Vice-Chancellors of other state universities in Bihar, Husain accepted the advice of the Chief Minister in the exercise of his powers as Chancellor and acted accordingly although he was opposed to the appointment of non-academicians as vice chancellors to universities.

Vice President of India (1962-1967)

On 14 April 1962, the Congress party chose Husain to be its candidate for the upcoming election to the office of theVice President of India

The vice president of India (IAST: ) is the deputy to the head of state of the Republic of India, i.e. the president of India. The office of vice president is the second-highest constitutional office after the president and ranks second in the ...

. The election was held on 7 May 1962, and votes counted the same day. Husain won 568 of 596 votes cast while his only rival NC Samantsinhar won 14 votes. He was sworn in as vice president on 13 May 1962.

In 1962, Husain was nominated the Vice President of the Sahitya Akademi

The Sahitya Akademi, India's National Academy of Letters, is an organisation dedicated to the promotion of literature in the languages of India. Founded on 12 March 1954, it is supported by, though independent of, the Indian government. Its of ...

– a post held by his predecessor S. Radhakrishnan before his election as President of India. The following year, he was awarded the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distinctio ...

. In 1965 he served briefly as the acting president when President Radhakrishnan left for the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

to undergo treatment for cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

. It was during his acting presidency that President's rule was reimposed in Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South ...

after elections held there the previous month failed to give any party a majority and efforts by the Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

to facilitate the formation of a government collapsed.

In 1966 Husain, as ex-officio Chairman of the Rajya Sabha

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

, gave a ruling that the parliamentary immunity from arrest would be limited to only civil cases and would not apply to criminal proceedings initiated against members.

President of India (1967 - 1969)

Husain was chosen as the Congress party's candidate to succeedDr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (; 5 September 1888 – 17 April 1975), natively Radhakrishnayya, was an Indian philosopher and statesman. He served as the 2nd President of India from 1962 to 1967. He also 1st Vice President of India from 1952 ...

as the President of India

The president of India ( IAST: ) is the head of state of the Republic of India. The president is the nominal head of the executive, the first citizen of the country, as well as the commander-in-chief of the Indian Armed Forces. Droupadi Mur ...

in the presidential election of 1967. There was a lack of enthusiasm for the candidature of Husain within the party, but Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

chose to nominate him as the party candidate over objections raised by K. Kamaraj

Kumaraswami Kamaraj (15 July 1903 – 2 October 1975, hinduonnet.com. 15–28 September 2001), popularly known as Kamarajar was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the Chief Minister of Madras State (Tamil Nadu) ...

, the party president, and other senior members of her cabinet. A coalition of seven opposition parties got the sitting Chief Justice of India, Koka Subbarao to resign his post and contest the election as their joint candidate. Unlike the three previous presidential elections, the election of 1967 proved to be a real contest between the various candidates. The campaign was marred by communal rhetoric and accusations of sectarianism being made against Husain by the Jana Sangh party. There was also speculation that Husain would lose on account of cross voting against him by Congress legislators, an outcome which would have forced the Prime Minister to resign.

There were 17 candidates in the fray for the election held on 6 May 1967. Of these, nine failed to win any vote. Husain won 4,71,244 votes against the 3,63,971 received by Subbarao. The margin of 1,07,273 votes was much larger than what was expected by the Congress party with Husain winning the most votes in Parliament and in twelve state legislatures including three where the Congress Party sat in the opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

. The results of the presidential election, coming after the general elections of 1967 where the Congress party had suffered severe setbacks, were seen as strengthening Prime Minister Gandhi. Husain was declared elected on 9 May 1967. His election as president was seen domestically as the Congress Party's attempt to reach out to the Muslims of India who had voted against it in the general elections and globally as burnishing India's claim of being a secular nation.

Husain was sworn in on 13 May 1967. In a memorable inaugural address, while dedicating himself to the service of the Indian nation and its civilization, Husain said The whole of Bharat is my home and its people are my family. The people have chosen to make me the head of this family for a certain time. It shall be my earnest endeavour to seek to make this home strong and beautiful, a worthy home for a great people engaged in the fascinating task of building up a just and prosperous and graceful life.Husain was the first Muslim and the first governor of a state to be elected President of India. Husain's election was challenged before the Supreme Court of India on the grounds that the result of the election had been affected by undue influence exerted by the Prime Minister. The

election petition

An election petition refers to the procedure for challenging the result of a Parliamentary election.

Outcomes

When a petition is lodged against an election return, there are 4 possible outcomes:

# The election is declared void. The result is q ...

filed by Baburao Patel was however dismissed by the court.

During his presidential tenure, Husain led state visits to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

. Husain, who had an interest in rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

s,is credited with having introduced several new varieties in the Mughal Gardens of the Rashtrapati Bhavan and building a glass conservatory for its collection of succulents

In botany, succulent plants, also known as succulents, are plants with parts that are thickened, fleshy, and engorged, usually to retain water in arid climates or soil conditions. The word ''succulent'' comes from the Latin word ''sucus'', meani ...

.

Death and funeral

heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

earlier in the year, was unwell after returning to Delhi from a tour of Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

on 26 April 1969. He died in the Rashtrapati Bhavan on 3 May 1969 of a heart attack. Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

V. V. Giri

Varahagiri Venkata Giri (; 10 August 1894 — 24 June 1980) was an Indian politician and activist from Berhampur in Odisha who served as the 4th president of India from 24 August 1969 to 24 August 1974. He also 3rd vice president of India from ...

was sworn in as acting president the same day. The Government of India declared thirteen days of national mourning

A national day of mourning is a day or days marked by mourning and memorial activities observed among the majority of a country's populace. They are designated by the national government. Such days include those marking the death or funeral of ...

. His body lay in state in the Durbar Hall of the Rashtrapati Bhavan where an estimated 200,000 people paid their tributes. The funeral was held on 5 May 1969. He is buried in the university campus of the Jamia Milia Islamia where his body was taken in a gun carriage in a ceremonial funeral procession

A funeral procession is a procession, usually in motor vehicles or by foot, from a funeral home or place of worship to the cemetery or crematorium. In earlier times the deceased was typically carried by male family members on a bier or in a cof ...

after the janaza prayers and the national salute being offered in the Rashtrapati Bhavan

The Rashtrapati Bhavan (, rāsh-truh-puh-ti bha-vun; ; originally Viceroy's House and later Government House) is the official residence of the President of India at the western end of Rajpath, Raisina Hill, New Delhi, India. Rashtrapati Bh ...

. Husain's death was mourned in Pakistan as well where flags flew at half mast

Half-mast or half-staff (American English) refers to a flag flying below the summit of a ship mast, a pole on land, or a pole on a building. In many countries this is seen as a symbol of respect, mourning, distress, or, in some cases, a salut ...

on the day of his funeral. Pakistan's President Yahya Khan sent the Chief of Air Staff of Pakistan Air Force

, "Be it deserts or seas; all lie under our wings" (traditional)

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = ...

and Deputy Chief Martial Law Administrator

The office of the Chief Martial Law Administrator was a senior and authoritative post with Zonal Martial Law Administrators as deputies created in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia that gave considerable executive authority and p ...

Air Marshal Malik Nur Khan

Air Marshal Malik Nur Khan Awan ( ur, ; 22 February 1923 – 15 December 2011) commonly known as Nur Khan, was a three-star air officer, politician, sports administrator, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Air Force, serving under ...

as his personal representative to the funeral. George Romney, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development

The United States secretary of housing and urban development (or HUD secretary) is the head of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, a member of the president's Cabinet, and thirteenth in the presidential line of succe ...

, represented President Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

whereas the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

was represented by its Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

. The Prime Ministers of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

too attended the funeral. Up to a million people are thought to have lined the streets as the funeral cortege

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engl ...

made its way to the burial ground. Husain was the first President to die in office and has served the shortest tenure in office.

Tomb

Husain's tomb was built in 1971 and was designed by Habib Rahman. Its architecture reflects the influence of Bauhaus aesthetics on traditional Indian styles as seen in its eight curved, reinforced concrete walls topped by rough cut

Husain's tomb was built in 1971 and was designed by Habib Rahman. Its architecture reflects the influence of Bauhaus aesthetics on traditional Indian styles as seen in its eight curved, reinforced concrete walls topped by rough cut marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

which have been inspired by Tughluq tombs. These tapering walls stand along a square plan to form an open structure topped by a shallow dome. The tomb has no ornamentation but features jali

A ''jali'' or jaali (''jālī'', meaning "net") is the term for a perforated stone or latticed screen, usually with an ornamental pattern constructed through the use of calligraphy, geometry or natural patterns. This form of architectural d ...

s and arches. The graves of Husain and his wife lie under the dome of the tomb.

Author

Husain wrote extensively inUrdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

''

Commemorative

Commemorative

"A Rose Called Zakir Hussain – A Life of Dedication", by Films Division, India, 1969 (Hindi)

BASIC NATIONAL EDUCATION: Report of the Zakir Husain Committee and the detailed syllabus with a foreword by Mahatma Gandhi.

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Husain, Zakir 1897 births 1969 deaths University of Allahabad alumni Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Recipients of the Bharat Ratna Governors of Bihar Indian Muslims Jamia Millia Islamia Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in public affairs People from Etawah Indian people of Pashtun descent People from Farrukhabad Presidents of India Vice presidents of India Politicians from Hyderabad, India Vice-Chancellors of the Aligarh Muslim University Burials in India Founders of Indian schools and colleges

''

Friedrich List

Georg Friedrich List (6 August 1789 – 30 November 1846) was a German-American economist who developed the "National System" of political economy. He was a forefather of the German historical school of economics, and argued for the German Custom ...

’s ''National System of Economics'', Edwin Cannan

Edwin Cannan (3 February 1861, Funchal, Madeira – 8 April 1935, Bournemouth), the son of David Cannan and artist Jane Cannan, was a British economist and historian of economic thought. He was a professor at the London School of Economics from 1 ...

’s ''Elements of Economics'' and Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

’s ''Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

''. He also wrote extensively on education in books such as ''Aala Taleem'', ''Hindustan me Taleem ki az Sar-E-Nau Tanzeem'', ''Qaumi Taleem'' and ''Taleemi Khutbat'' and on Urdu poets Altaf Hussain Hali in ''Hali: Muhibb-e-Wata''n and Mirza Ghalib

)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Kala Mahal, Agra, Maratha Confederacy

, death_date =

, death_place = Gali Qasim Jaan, Ballimaran, Chandni Chowk, Delhi, British India

, occupation = Poet

, language ...

in ''Intikhab-e-Ghalib''. Husain wrote several stories for children which he published under a nom de plume

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

. These include ''Uqab aur Doosri Kahaniyan'' and stories translated into English and published under The Magic Key series by Zubaan Books. ''Capitalism: An Essay in Understanding'' is a series of lectures he delivered at the Delhi University

Delhi University (DU), formally the University of Delhi, is a collegiate central university located in New Delhi, India. It was founded in 1922 by an Act of the Central Legislative Assembly and is recognized as an Institute of Eminence (IoE) ...

in 1946. His convocation addresses were published in 1965 as ''The Dynamic University''. As President of India, Husain headed a committee to celebrate the Ghalib Centenary in 1969 which recommended the establishment of the Ghalib Institute as a memorial to Ghalib whereas the Ghalib Academy in Delhi was inaugurated by Husain in 1969.

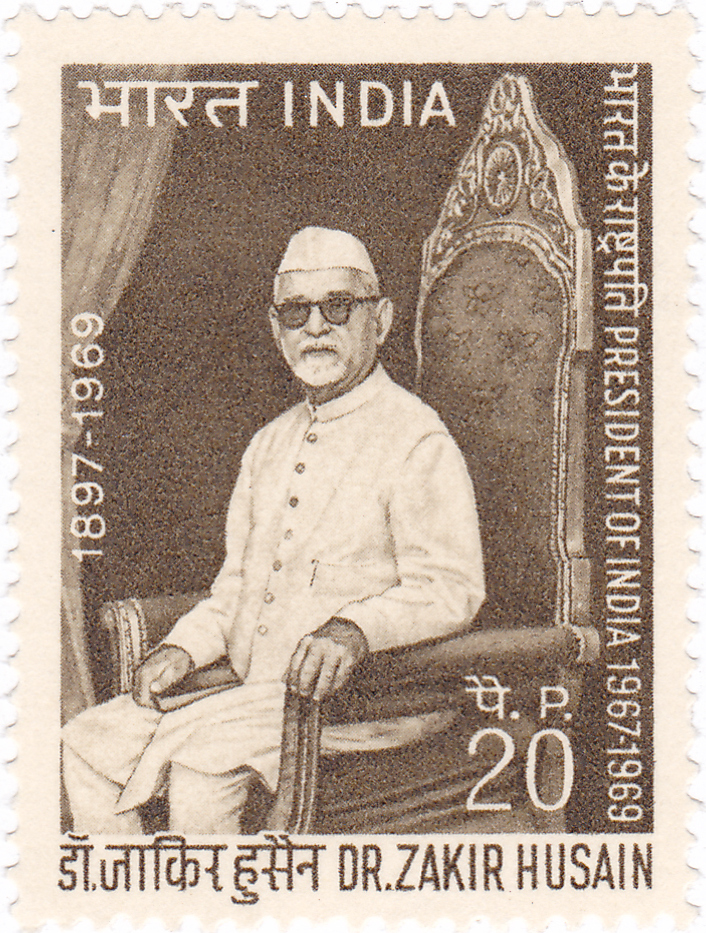

Commemoration

Commemorative

Commemorative postage stamps

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the f ...

on Husain were issued by India Post

India Post is a government-operated postal system in India, part of the Department of Post under the Ministry of Communications. Generally known as the Post Office, it is the most widely distributed postal system in the world. Warren Hastings ...

in 1969 and 1998.

"A Rose Called Zakir Hussain – A Life of Dedication" is a 1969 documentary film

A documentary film or documentary is a non-fictional motion-picture intended to "document reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction, education or maintaining a historical record". Bill Nichols has characterized the documentary in te ...

on the life of Husain produced by the Films Division of India

The Films Division of India (FDI), commonly referred as Films Division, was established in 1948 following the independence of India. It was the first state film production and distribution unit, under the Ministry of Information and Broadcastin ...

. In 1975 the Delhi College, a constituent college

A collegiate university is a university in which functions are divided between a central administration and a number of constituent colleges. Historically, the first collegiate university was the University of Paris and its first college was the C ...

of the Delhi University

Delhi University (DU), formally the University of Delhi, is a collegiate central university located in New Delhi, India. It was founded in 1922 by an Act of the Central Legislative Assembly and is recognized as an Institute of Eminence (IoE) ...

, was renamed the Zakir Hussain College. The Zakir Husain Centre for Educational Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University

Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) is a public major research university located in New Delhi, India. It was established in 1969 and named after Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first Prime Minister. The university is known for leading faculties and r ...

and the Dr. Zakir Husain Central Library of the Jamia Milia Islamia are also named after him. Delhi's Wellesley Road was renamed the Dr. Zakir Hussain Marg. The Zakir Hussain Rose Garden

Zakir Hussain Rose Garden, is a botanical garden in Chandigarh, India and spread over of land, with 50,000 rose-bushes of 1600 different species. Named after India's former president, Zakir Hussain and created in 1967 under the guidance of ...

in Chandigarh

Chandigarh () is a planned city in India. Chandigarh is bordered by the state of Punjab to the west and the south, and by the state of Haryana to the east. It constitutes the bulk of the Chandigarh Capital Region or Greater Chandigarh, which a ...

, which is Asia's largest rose garden

A rose garden or rosarium is a garden or park, often open to the public, used to present and grow various types of garden roses, and sometimes rose species. Most often it is a section of a larger garden. Designs vary tremendously and roses m ...

, is also named after Hussain. ''Dr. Zakir Hussain - Teacher who became President'', a book on Husain by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations

The Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), is an autonomous organisation of the Government of India, involved in India's global cultural relations, through cultural exchange with other countries and their people. It was founded on 9 Apri ...

, was released in 2000.

Notes

References

External links

"A Rose Called Zakir Hussain – A Life of Dedication", by Films Division, India, 1969 (Hindi)

BASIC NATIONAL EDUCATION: Report of the Zakir Husain Committee and the detailed syllabus with a foreword by Mahatma Gandhi.

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Husain, Zakir 1897 births 1969 deaths University of Allahabad alumni Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Recipients of the Bharat Ratna Governors of Bihar Indian Muslims Jamia Millia Islamia Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in public affairs People from Etawah Indian people of Pashtun descent People from Farrukhabad Presidents of India Vice presidents of India Politicians from Hyderabad, India Vice-Chancellors of the Aligarh Muslim University Burials in India Founders of Indian schools and colleges